Borrowing Ideas From 3 Interesting *Internal* Classes in the .NET 3.5 Framework To Help Control "Goo" In Your Code

As programmers, we often have to concern ourselves with scaffolding “goo” in our code as in the start of the System.Collections.Queue.CopyTo method:

public virtual void CopyTo(Array array, int index)

{

if (array == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("array");

}

if (array.Rank != 1)

{

throw new ArgumentException(Environment.GetResourceString("Arg_RankMultiDimNotSupported"));

}

if (index < 0)

{

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException("index", Environment.GetResourceString("ArgumentOutOfRange_Index"));

}

if ((array.Length - index) < this._size)

{

throw new ArgumentException(Environment.GetResourceString("Argument_InvalidOffLen"));

}

}All of the checking is considered a best practice in our field. We are taught to never trust input and to be paranoid about what get into our functions.

But it took 16 lines! I’m always on the lookout for how to improve my code writing on gooey areas like this. Recently I was doing some reflectoring into the .NET 3.5 framework and noticed two helper internal classes that the smart folks on the LINQ team created to help get their job done:

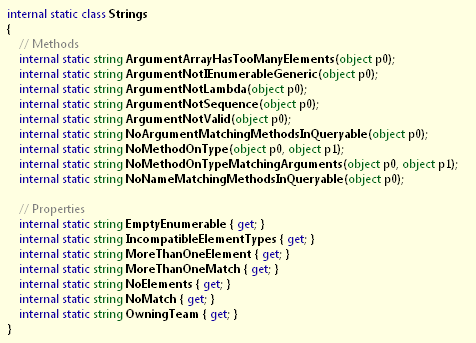

Exhibit A: System.Linq.Strings

Our first stop takes us to generating error messages to give to the user. We’re told that it’s a best practice to always use resources for strings that are visible to a user and this helper class makes it easy to do that so that we can write statements like

throw new ArgumentException(Strings.ArgumentNotIEnumerableGeneric(p0));Doesn’t that last line just feel better than something like the CopyTo way of “

throw new ArgumentException(Environment.GetResourceString("ArgumentNotIEnumerableGeneric"));?

Furthermore, it helps to insulate you from the ramifications of renaming a resource. It also lets you use IntelliSense while writing code and lets you use easily refactoring tools if you want to change the name later.

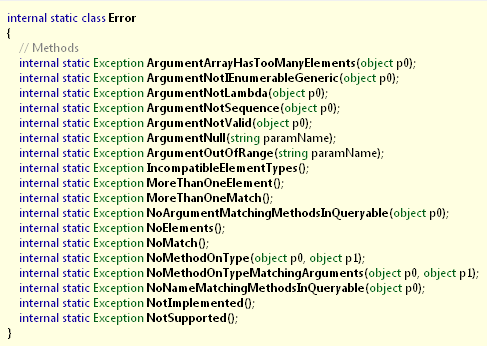

Exhibit B: System.Linq.Error

The team went one further and created another helper class to create error messages based off the Strings class as in:

internal static Exception ArgumentNotIEnumerableGeneric(object p0)

{

return new ArgumentException(Strings.ArgumentNotIEnumerableGeneric(p0));

}Once you have this class, you can now have lines like this one from the System.Linq.Queryable.AsQueryable method:

if (type == null)

{

throw Error.ArgumentNotIEnumerableGeneric("source");

}To me, that looks much more readable/declarative/maintainable/fluent than how Queue.CopyTo does the same type of thing.

This comes to the limit of where the Linq team took it and which brings us to the final internal class of note.

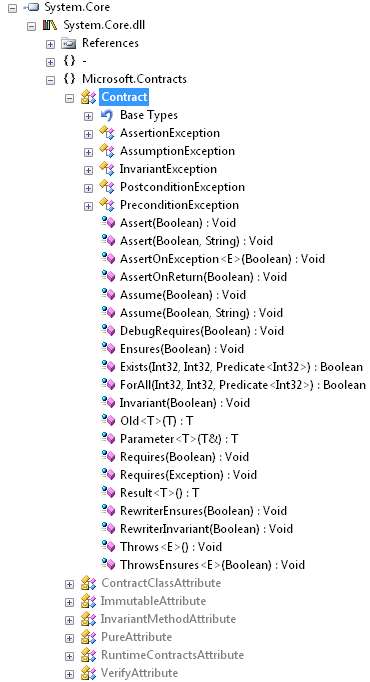

Exhibit C: Microsoft.Contracts.Contract

The Contract class has some interesting use in 3.5 classes as in a constructor of (the unfortunately also internal class) System.Numerics.BigInteger:

Contract.Requires(_data != null);

Contract.Requires((_sign >= -1) && (_sign <= 1));This is a bit more declarative than the Linq way, but also achieves roughly the same goal since Requires has this implementation:

public static void Requires(bool b)

{

if (!b)

{

throw new PreconditionException();

}

}It seems that if we combined the best of both of the ideas from the two teams, we’d get something like this:

internal static class Guard

{

internal static void ArgumentNotNull(object value, string paramName)

{

if (value == null)

{

throw Error.ArgumentNull(paramName);

}

}

}This allows for this usage: “Guard.ArgumentNotNull(data, “data”);” which would throw the correct exception. Now, anywhere in your code where you want to require that an argument isn’t null, you simply call this method. As an added benefit, by right clicking on the “ArgumentNotNull” method in Visual Studio, you can find all references to see where you had to do that check in your code. Better still, is that you fall into the Pit of Success of doing the right thing by doing less work!

You could use something like the Enterprise Library’s Validation Application Block to achieve similar results, but the “Guard” approach seems very simple and especially useful when you can’t use other libraries for one reason or another.

It’s clear that Microsoft.Contracts.Contract was inspired by the Spec# project as seen in the attributes and method bodies of some methods like “Invariant”:

[Pure, Conditional("USE_SPECSHARP_ASSEMBLY_REWRITER")]

public static void Invariant(bool b)

{

string text1 = "This method will be modified to the following after rewriting:" + "if (!b) throw new InvariantException();";

}I believe that C# 4.0 (or possible 5.0) will bring in Spec#’s ideas to the masses to allow for things like:

class ArrayList

{

void Insert(int index , object value)

requires 0 <= index && index <= Count otherwise ArgumentOutOfRangeException;

requires !IsReadOnly && !IsFixedSize otherwise NotSupportedException;

ensures Count == old(Count) + 1;

ensures value == this[index];

ensures Forall{int i in 0 : index ; old(this[i]) == this[i]};

ensures Forall{int i in index : old(Count); old(this[i]) == this[i + 1]};

{

...

}

}All of which will surely make code more reliable through static analysis if used correctly.

At the very least, it’s good to see the gems tucked away in the internal classes of the framework to see how things like Strings, Error, and Contract/Guard can make even your C# 2.0 code look better.

What do you think? What types of helper classes do you use to make your code have less “goo?”

UPDATE: Thanks to “Tweezz” in the comments for pointing out the general idea for Guard goes back to Eiffel’s trademarked “Design by Contract” philosophy.

UPDATE 2: The internal class System.Data.ExceptionBuilder does the same thing as System.Linq.Errors, but doesn’t punt to a Strings equivalent class.

UPDATE 3: Andrew Matthews has some interesting applications of Design by Contract using C# 3.0. Check it out here.

P.S. Thanks to my coworker, Dan Rigsby, for introducing me to the “Guard” class idea!