Back from the Future Bugs

(In honor of this quasi-historic day, I wanted to share my most memorable bug.)

Ordinary software bugs are merely annoying but straightforward to find and fix. Legendary bugs are the ones that actively resist being found and make you question your sanity for prolonged periods of time.

In early 2011, I was working on Kaggle’s submission handling code. Kaggle hosts competitions where the goal is to make the best predictions on a dataset. For example, given an image of a person’s retina, determine if they’re suffering damage from diabetes. You upload your predictions and they get evaluated against the known (but private) solution in order to compute your score which shows up on a leaderboard.

Long after deploying the submission handling code, a user emailed us saying that his score didn’t appear on the leaderboard. When I went to investigate, I saw his score was indeed on the leaderboard. I tried to reproduce his issue in production and I couldn’t. I painstakingly verified everything in a local debugger session and it worked perfectly without any issue. Given that everything seemed to be working fine, I closed the issue because I couldn’t reproduce it.

Much time passed without any further problems.

And then, it happened again: another user reported that their score didn’t appear on the leaderboard. This time I was convinced that there was some genuine edge case causing the issue. I once again carefully went through the whole submission process in a debugger and couldn’t replicate it. At this point, I was sure it was some weird database issue. Perhaps some obscure exception was thrown that caused the database to never update. I added some checks and exception handling code and the problem seemed to go away.

But in June of 2014, it came back with a vengeance. A new developer on the team was handling support requests at the time and received several reports of submissions not showing up on the leaderboard. When he explained the bug report, I was immediately haunted by memories of it. I recounted the mystery of this bug and how I couldn’t reproduce the issue. In frustration, I suggested that he add code to manually force an update to the leaderboard to workaround this bug.

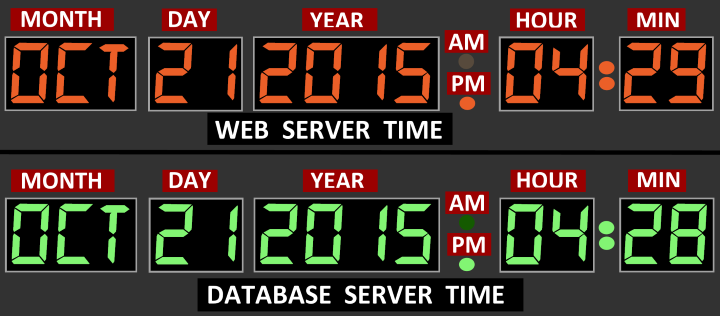

I was disgusted by my own suggestion. It wasn’t a fix, it was duct-taping around the issue. But soon after offering this advice I had the forehead-slapping moment: different clocks can have different time!

It’s embarrassingly obvious in hindsight.

Here’s what happened:

- When the submission was created, I set its status to “pending” and set its timestamp to the current time of the web server.

- Another machine dequeued the submission, calculated its score, and then sent the result back.

- The web server then updated the status of the submission which caused a stored procedure in the database to update the leaderboard based on all the submissions up to the current time of the database server.

The reason why I could never reproduce this problem locally was because my local web server and database server were on the same physical machine with the same clock, so the results were always consistent. Further, most of the time the clocks on the web server and database server in production were carefully synchronized over the network to within a few milliseconds of each other.

This bug only surfaced when:

- The database server’s clock had drifted a second or two behind the web server’s clock.

- The submission processing time took less time than the amount of drift between the two machines.

- The database recalculated the leaderboard based on all submissions up to its current time and thus ignored the submission that was in its perceived future.

- No subsequent submissions happened that would have forced another leaderboard recalculation based on the then current time.

Once I understood it was a clock drift bug, there was very simple fix: always use the same clock. In this case, we chose to always use the same database clock and haven’t had a problem with it in well over a million submissions since then.

In hindsight, it was a distributed systems rookie mistake. I had painfully rediscovered Segal’s law: “A man with a watch knows what time it is. A man with two watches is never sure.”

In addition to the simple solution we chose of always using the same physical clock, you can get around this problem by using fancier techniques like vector clocks or TrueTime in Google’s Spanner database that uses GPS synchronized clocks to carefully keep track of the uncertainty of the current time in order to provide transactional consistency across the planet.

As we increasingly write software that executes across multiple machines, it’s important to have some strategy for handling clock drift (even if it’s less than a second). Because, if you don’t, you too might be bitten by bugs caused from data that’s coming back… from the future.