SKU Driven Development

I like ice cream. Sure, I like enjoying a coffee cup filled with ice cream after working out at the gym (and sometimes even when I don’t), but I also enjoy its perceived simplicity. All of my favorite flavors have some form of vanilla base with something added to it. For example, Fudge Tracks to me is vanilla + chocolate + peanut butter. Cookie Dough is, unsurprisingly, vanilla + cookie dough + chocolate.

I like ice cream. Sure, I like enjoying a coffee cup filled with ice cream after working out at the gym (and sometimes even when I don’t), but I also enjoy its perceived simplicity. All of my favorite flavors have some form of vanilla base with something added to it. For example, Fudge Tracks to me is vanilla + chocolate + peanut butter. Cookie Dough is, unsurprisingly, vanilla + cookie dough + chocolate.

I said “perceived” simplicity because my father-in-law works in the ice cream business and I know there are lots of smart people in the lab working on formulas and many people that design the manufacturing processes to ensure the final result “just right.” There are lots of little “gotchas” too. For example, when adding cookie dough, you might have to reduce the butterfat content to keep the nutrition label from scaring people. Also, many people (e.g. me) think that everything starts with vanilla, but it’s really a “white base” that may or may not have vanilla in it.

But despite all of the little details under the covers, ice cream still has a simplicity that our grandmas can understand. As I work more with software professionally, I’m becoming more convinced that if your architecture is too complicated that you couldn’t realistically explain it at a high level to your grandma (while she’s not taking a nap that is), it’s probably too complicated.

My favorite ice cream flavors all start out roughly the same, but then get altered by the addition of things. The end result is a unique product that has its own Universal Product Code (UPC) on its container. Can we make software development that simple? Can we start with some core essence like vanilla ice cream and create various versions of products, each with its own unique Stock Keeping Unit (SKU)?

This idea isn’t foreign to our industry. Microsoft has at least five different SKUs of Vista and Visual Studio has over 10. The test is, could we as developers of products with much smaller distribution create different SKUs of our software? More importantly, even if we only planned to sell one version of our software, would it still be worth putting an emphasis on thinking in terms of partitioning our product it into several “SKUs?”

I am starting to think that there might be merit in it. What will it take to think that way? I think it requires just a teeny bit of math.

The Calculus of SKU Driven Development

Even as a math major in college, I never really got excited about calculus or its related classes like differential equations. It tended to deal with things that were “continuous” whereas my more dominant computer science mind liked “discrete” things that I could count. With whole numbers, I could do public key cryptography or count the number of steps required in an algorithm. With “continuous” math, I could do things like calculate the exact concentration of salt in leaky tank of water that was being filled with fresh water. In my mind, salt doesn’t compare with keeping secrets between Alice and Bob.

Although I could answer most of the homework and test problems in calculus, I never really internalized or “connected with” it or its notation of things like “derivatives.”

That is, until this week.

While trying to find a solution to the nagging feeling that software could be simpler, I came across a fascinating paper that was hidden away with the title of “Feature oriented refactoring of legacy applications.” It had a list of eight equations that had an initial scary calculus feel to them. But after the fourth reading or so, they really came alive:

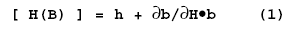

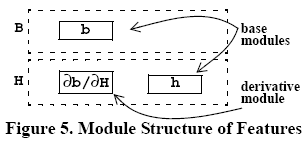

The first equation essentially says that if you want to make something like Cookie Dough Ice Cream (here labeled “H”) from your vanilla base product (labeled “B”), you’ll need… cookie dough! See? Math is simple. The actual cookie dough is expressed by “h.” The “db/dh” part is telling us “here’s how you have to modify the vanilla ice cream base when you’re making Cookie Dough to keep the nutrition reasonable.” The letter “b” is simply the raw vanilla ice cream base. The “*” operator says “take the instructions for how to modify the base and actually do them on the base.” Very intuitive if you think about it. The only trick is that uppercase letters represents SKUs (aka “Features”) and lowercase letters represent the ingredients (or “modules”) in that SKU. The paper was nice enough to include this picture to visualize this:

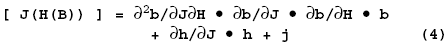

We’ll skip to the last significant equation. It is also the most scary looking, but it’s just as simple:

The scary part is that if we want to to add chocolate chips, “j”, to our existing Cookie Dough Ice Cream, “H(B)”, we will start to see a “2” superscript, called a “second order derivative.” The “d2b/(dJdH)” just means that “if I have both chocolate chips and cookie dough, I’ll need to lower the butterfat content of the vanilla base even more to make the nutrition label not scare people.” Then, make the cookie dough healthier to allow for the chocolate chips (dh/dJ) and then finally add the chocolate chips (j). That is, say that if I just added chocolate chips to vanilla (db/dJ), I’d only have to lower the vanilla butterfat by 5%. Similarly, if I just added cookie dough, I’d have to lower the butterfat by 7%. If I have both chocolate chips and cookie dough, I have to lower the butterfat an additional 3% (d2b/(dJdH)) for a total butterfat lowering of 3 + 5 + 7 = 15%.

Why Software Development Can Be Frustrating

The above calculus shows, in a sort of sterile way, why developing software can frustrate both you as a developer and as a result, your customers. The fundamental philosophy of SKU Driven Development is that you absolutely, positively, must keep your derivatives (first order and higher) as small as humanly possible with zero being your goal. If you don’t, you’ll feel tension and sometimes even pain.

It starts off with the marketing guys telling you that customers really want SKU “J” of your product because they really need all that “j” will give them. Moreover, your top competitors have promised to have “j” and if you don’t add it to your existing product, “H(B)”, then customers have threatened to jump ship.

So management gets together and then eventually asks you their favorite question: “how long will it take to make SKU ‘J’ of our product? How much will it cost?” Enlightened by the calculus above, you look at equation 4 and then count every time where you see “J.” These items denotes changes to the existing code. The final “j” represents the actual additional feature that marketing wants.

You’ll likely have a conversation like this: “well, we can’t just add ‘j.’ We need to change our core library to get ready for J, and update this user control to get ready for J, oh and then we’d need update this menu and that toolbar and this context menu and this documentation, oh yeah and then make sure that we didn’t cause a regression of any of the functionality in our existing product, H(B), and then finally we could add ‘j’ and then test and document it.”

Sure, you didn’t use nice simple letters like “J”, but that’s what makes math so elegantly expressive. It doesn’t matter what “J” is, the math doesn’t lie.

Here’s another pain point: let’s say that in testing feature #4 of your product, a lot of bugs came up and moreover, marketing has proven beyond a reasonable doubt that no one even cares about feature #4. It was just some silly feature that a programmer added to feel more macho. Feature #4 is stopping your company from shipping and making any more money. You have to cut it! “Go, cut it out! Here’s a knife” they shout to you.

“But, it’s not that simple!” you reply.

“Why not? It’s just as if I told you to make a version of a car that has an option to not have a GPS, or a TV, or cruise control, or rear defrost. The auto industry has been doing this for decades. Why can’t you do it? Is this too much to ask!? Don’t get in the way of my next bonus buddy!”

Ok, it’s usually more peaceful than that. Well, usually anyway.

You can’t just remove feature #4, “F4”, because your product is now P = F6(F5(F4(F3(F2(F1(B)))))). Right about this time, you can feel the weight of all the derivatives. They are going to drive you to do a lot of searching and testing. It’s not that you’re a bad programmer, it’s just that in programs that haven’t been built with the “SKU Driven Development” philosophy in mind tend to have higher amounts of derivatives. Usually, derivatives that could be almost zero are much higher and therefore cost you time and your company money.

Is There Any Hope?

I use the term “SKU Driven Development” because, as I write this, it has zero matches on Google. This is a good thing because it means I can define to be what I choose it to mean. To me, SKU Driven Development is a software development philosophy that has the following four principles:

- Always have a “get the product to market” mentality by thinking in terms of shipping a new “SKU” that has the additional functionality. This makes it easier to think of your product in a more natural way of adding and removing options like people can do with ice cream and cars.

- Build your product in such a way that derivatives are as small as possible. You want them to be zero. This is not always possible, but that’s your goal. It is extremely important to have higher order derivatives small. I think that a developer should seriously think about his or her architecture if it requires significant second order derivatives. Furthermore, a software architect should be forced to give a rigorous defense of why their architecture necessitates third order or higher derivatives and convincingly prove there is no other reasonable way that wouldn’t sacrifice something else that is more important.

- Your product should be stripped down to some fundamental “core” SKU where further functionality can’t be stripped or it ceases to be meaningful. This is sort of like a car with an engine and seats, but no air conditioning, radio, clock, cruise control, etc. Only once you have stripped things down to the core can you start to think in terms of additive SKUs.

- Each piece of new functionality and every derivative that it necessitates must be testable. This principle ensures that a quality product continues to be a quality product, even with the additional functionality.

The problem isn’t that our industry hasn’t thought about this; the problem is that there are many different things to “keep in mind” while trying to achieve it. As developers, we have many tools that can help:

- Object Oriented Programming and Component-Based Software Engineering help think of the world in higher level pieces rather than individual functions or methods.

- Software Platforms / Frameworks like the .NET Framework and Rails help one have a richer base of functionality to start with. This is the “B” in the calculus.

- Aspect Oriented Programming (AOP)is a way of cleanly describing and injecting a change to an existing code base.

- Feature Oriented Programming (FOP) is a way expressing programs in terms of “features.” It was from a FOP paper that I “borrowed” the calculus.

- Separation of Concerns is a concept that has you break up programs “into distinct features that overlap in functionality as little as possible.”

- Refactoring is a technique to take the product as you have it today and make it more SKU oriented.

- Product Line Architecture which includes things like:

- Software Design Patterns like the Strategy, Observer, Model View Controller, and Model View Presenter patterns. This leads to things like the fancy new ASP.NET MVC Framework

- Test Driven Development (TDD) helps you achieve principle #4 by having you ensure that changes and additions are tested by creating a test first.

- Behavior Driven Design (BDD) extends TDD to a higher level focusing on end functionality of what the application should do.

- Mixins in languages like Ruby and Scala allow you to add functionality to a class in parts. It’s like adding interfaces to a class, but the interfaces can have functionality. This is sort of like multiple inheritance, but cleaner.

- Plugins and technologies like .NET’s System.Addin classes make it easier to build an application out of many parts.

- Dependency Injection can help make your app more customizable by allowing you to easily switch implementations of pieces.

- Inversion of Control (IoC) helps developers apply the Hollywood Principle of “don’t call us, we’ll call you.” This helps designing components that can be added to other products easily and therefore help to create SKUs more readily.

- The Composite UI Application Block (CAB) and Smart Client Software Factory (SCSF) ideas and tools help blend components together into a cohesive end product.

- Monads came from the functional programming where they’ve been in use in languages like Haskell for years. They help add functionality to some core concept in a nice way. They’re starting to be introduced into the mainstream now with LINQ and its future evolutions. There is nothing to fear about them; it’s just that they have an unfortunate sounding name.

- Processes like Scrum help ensure that you develop meaningful SKUs on a regular schedule.

…

The list could go on and on.

Having all of these things that we have to “keep in mind” as developers makes it hard to keep up. But, it’s also why we’re paid to do what we do. Marketing wants to give us a Marketing Requirements Document (MRD) with additional features F1, F2, F3, and we’re paid to turn our existing product, B, into F3(F2(F1(B))). It’s not as easy as we’d like (f1 + f2 + f3) because all of those derivatives get in the way.

There’s no silver bullet and its unlikely that completely derivative free programming will ever be possible for real applications. SKU Driven Development isn’t prescriptive beyond the four principles I outlined above. It’s sort of a “try your best, but keep these overarching goals in mind.” Academics are already showing inroads into how it might be possible with simple examples and things like AHEAD.

It’s going to take time. I’m going to try to head towards the SKU mentality. I’ll probably going to go down the wrong path many times. I’ll probably create or at least suggest of designs that are too complicated and don’t stand up to growth and maintainability. Over the years I want to get better, but I don’t see of a clear path there yet. It will probably involve using some of the tools I outlined above.

Lots of things to think about and “keep in mind” while enjoying my next bowl of ice cream.