Boy Scout Check-ins

I missed the Boy Scouts callout when I was kid. Perhaps that’s why it took me 20 years to figure out a knot that keeps my shoes tied all day. My recent attempt at starting a campfire required a propane torch. Despite my shortcomings, I felt a connection to the Scouts while reading this:

It’s not enough to write the code well. The code has to be kept clean over time. We’ve all seen code rot and degrade as time passes. So we must take an active role in preventing this degradation.

The Boy Scouts of America have a simple rule that we can apply to our profession.

If we all checked-in our code a little cleaner than when we checked it out, the code simply could not rot. The cleanup doesn’t have to be something big. Change one variable name for the better, break up one function that’s a little too large, eliminate one small bit of duplication, clean up one composite ‘if’ statement.

Can you imagine working on a project where the code simply got better as time passed? Do you believe that any other option is professional? Indeed, isn’t continuous improvement an intrinsic part of professionalism? [Clean Code, p14]

While reading this, I was reminded of another gem:

Well-designed code looks obvious, but it probably took an awful lot of thought (and a lot of refactoring) to make it that simple. [Code Craft, p247]

Both sound great, but they have a sort of “Don’t forget to floss” ring to them.

We’ve heard for years that refactoring helps improve code, but actually doing it can sometimes feel too daunting. It’s just a fact that a lot of the code we deal with on a daily basis doesn’t have enough test coverage, if there are any tests at all, to have us feel fully confident with many changes that we make to our code.

But a Scout wouldn’t let the sad state of some parts of the code get him down. A Scout would always have his nose out for stinky code to clean up so that he could get a teeny bit of satisfaction knowing that he checked-in code that was better than when he checked it out.

This isn’t a new idea; it’s just a matter of realizing how easy it is.

Examples

There’s a lot of low-hanging fruit in a typical code base. Over months of development, the top of a C# file might look like this:

using System.Linq;

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using Moserware.IO;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.Text.RegularExpressions;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;This is a messy way to introduce your code. With just a simple click in Visual Studio, you can have it automatically remove clutter and sort things to get something nicer:

using System.Text.RegularExpressions;

using System.Threading;

using Moserware.IO;For a three second time investment, you’ll leave the file slightly better than you found it. With a free add-in, you can do this for your entire project in about the same amount of time.

Different team members can often work in the same class and you’ll end up with member variable declarations that identify each person’s style:

public class CircularBuffer<T>

{

T[] m_array;

private object syncRoot = new object();

private int _HeadIndex;

private int m_TailIndex;

...This can easily be made consistent in few seconds:

public class CircularBuffer<T>

{

private T[] _Array;

private int _HeadIndex;

private int _TailIndex;

private object _SyncRoot = new object();

...Changing a line like this:

if((i >= minAmount) && (i <= maxAmount))to use number-line order:

if((minAmount <= i) && (i <= maxAmount))makes the code slightly more visual and easier to read.

Introducing an explaining variable can turn:

private static DateTime GetElectionDay(int year)

{

DateTime startDate = new DateTime(year, 11, 1);

// Get the first Tuesday following the first Monday

if (startDate.DayOfWeek <= DayOfWeek.Monday)

{

// Current day of the week is before Tuesday

return startDate.AddDays(DayOfWeek.Tuesday - startDate.DayOfWeek);

}

else

{

// Current day of the week is Tuesday or after

return startDate.AddDays(7 - (startDate.DayOfWeek - DayOfWeek.Tuesday));

}

}into a slightly more maintainable version that doesn’t need comments:

private static DateTime GetElectionDay(int year)

{

DateTime nov1 = new DateTime(year, 11, 1);

int daysUntilMonday;

if (nov1.DayOfWeek < DayOfWeek.Tuesday)

{

daysUntilMonday = DayOfWeek.Monday - nov1.DayOfWeek;

}

else

{

daysUntilMonday = 6 - (nov1.DayOfWeek - DayOfWeek.Tuesday);

}

DateTime firstMonday = nov1.AddDays(daysUntilMonday);

return firstMonday.AddDays(1);

}Along these lines, I tend to agree with Steve Yegge’s observation:

The [Refactoring] book next tells me: don’t comment my code. Insanity again! But once again, his explanation makes sense. I resolve to stop writing one-line comments, and to start making more descriptive function and parameter names.

By themselves, each of these refactorings almost seems too simple. But each leaves your code in a slightly better place than you found it thereby qualify as a “Boy Scout Check-In.”

Be Careful

We’ve probably all heard horror stories of some poor programmer who changed just “one little character” of code and caused rockets to explode or billion dollar security bugs. My advice is to not let that be you. Write more tests and use code reviews if that helps. Just don’t let it be an excuse to not do something.

Boy Scout Check-ins should be short and measured in minutes for how long they take. Get in and out with slightly better code that fixed one small thing. Try hard not to fix a bug or add a feature while doing these small check-ins or you might face the wrath of your coworkers as Raymond Chen points out:

Whatever your changes are, go nuts. All I ask is that you restrict them to “layout-only” check-ins. In other words, if you want to do some source code reformatting and change some code, please split it up into two check-ins, one that does the reformatting and the other that changes the code.

Otherwise, I end up staring at a diff of 1500 changed lines of source code, 1498 of which are just reformatting, and 2 of which actually changed something. Finding those two lines is not fun.

Avoid Cycles

One subtle thing to realize is that you don’t want to get lost in an infinite loop with a coworker of mutually exclusive changes. This is easy since good people can disagree. For instance, compare:

Use ‘final’ or ‘const’ when possible By declaring a variable to be final in Java or const in C++, you can prevent the variable from being assigned a value after it’s initialized. The final and const keywords are useful for defining class constants, input-only parameters, and any local variables whose values are intended to remain unchanged after initialization. [Code Complete 2, p243]

and

I also deleted all the ‘final’ keywords in arguments and variable declarations. As far as I could tell, they added no real value but did add to the clutter. Eliminating ‘final’ flies in the face of some conventional wisdom. For example, Robert Simmons strongly recommends us to “… spread final all over your code.” Clearly I disagree. I think there are a few good uses for ‘final’, such as the occasional ‘final’ constant, but otherwise the keyword adds little value and creates a lot of clutter. [Clean Code, p276]

Don’t get bogged down with someone else on adding and removing ‘final’ or ‘readonly’. Just be consistent.

I’m embarrassed to admit that in my earlier days, I might have “cleaned” code like this:

string headerHtml = "<h1>" + headerText + "</h1>";into

string headerHtml = String.Concat("<h1>", headerText, "</h1>");or even worse:

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

sb.Append("<h1>");

sb.Append(headerText);

sb.Append("</h1>");

string headerHtml = sb.ToString();In this first case, I thought I was brilliant because I knew about the Concat method and thought it’d give me faster code. This is not true because the C# compiler special cases string concatenation to automatically do this. The second example is painful because it’s uglier and slower and it isn’t building a string in a loop where StringBuilders make a lot of sense.

After many dumb mistakes like this, I’ve finally decided that if I ever have a doubt on which option to use, I’ll pick the more readable one:

Write your code to be read. By humans. Easily. The compiler will be able to cope. [Code Craft, p59]

Coda

Boy Scout check-ins are small steps that help fix the broken windows that we all have in our code. When you look at your code, try to find at least one thing you can do to leave it better. Eventually it becomes a game where everyone benefits. These check-ins can often be a small reward for checking-in a large feature or fixing a nasty bug.

Boy Scout check-ins are small steps that help fix the broken windows that we all have in our code. When you look at your code, try to find at least one thing you can do to leave it better. Eventually it becomes a game where everyone benefits. These check-ins can often be a small reward for checking-in a large feature or fixing a nasty bug.

If you’re pressed for time and can’t make the change now or you want to save it for when you can make the change across all your code, make a note to yourself. I create empty change-lists in my version control system for this purpose. This is also helpful if you find a bug and want to later complained that hand-washing took too long and “wasted” their precious time. We all have our own pressures that might cause us to think that we can neglect basic code hygiene. Over time, this snowballs into a mess that we’ve all had to deal with.

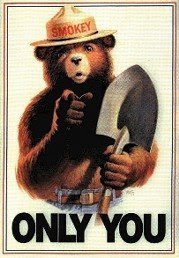

Only you can make a difference in your code campground.