The Private Life of a Public API

In college, I’d add “public” in front of my classes and methods without giving it much thought. Sure, I knew about “protected” and “private” and would use them where it made sense, but I had no pragmatic experience of designing my “public” code so that other people could easily use it.

Even a few years after graduation, I still didn’t have to worry much about creating a public Application Programmer Interface (API). As it turned out, I was often the only “Programmer” that my code had to “Interface” with.

But I had a dream.

I knew that if I really wanted to get better as a programmer, I would have to write code that others could easily reuse. About two years ago, I started using Reflector to make some serious study of the internals of the .NET Framework. It was great to be able to do deep “reflectorings” on a real framework that is used by millions of people and see its good parts and its mistakes.

My next big step was following the recommendations of several blogs and reviews by buying a copy of Framework Design Guidelines by Krzysztof Cwalina and Brad Abrams. It’s full of practical advice that explicitly points out how the .NET framework itself was intentionally designed. I found the book to be helpful enough that I really wanted to be a reviewer of the second edition. I didn’t make the cut, but the publisher was kind and sent me a copy of it. I spent the past few days reading the new edition searching for updates. In the process, I also reflected on the older, but still relevant, guidelines from the first edition.

One of my favorite parts of the book is that it is full of annotations from the people in the trenches that actually designed the framework. For example:

“If you say what your library does and ask a developer to write a program against what he or she expects such a library to look like (without actually looking at your library), does the developer come up with something substantially similar to what you’ve produced? Do this with a few developers. If the majority of them write similar things without matching what you’ve produced, they’re right, you’re wrong, and your library should be updated appropriately.” - Chris Sells, p.3

The book continues with many details of the work that goes into creating a public API and it helps shed some light an API beyond its short IntellSense description.

It’s FileName, not Filename. Ok?

The design guidelines don’t hide their goal:

“Consistency is the key characteristic of a well-designed framework… Consistency is probably the main theme of this book. Almost every single guideline is partially motivated by consistency…” - p.6

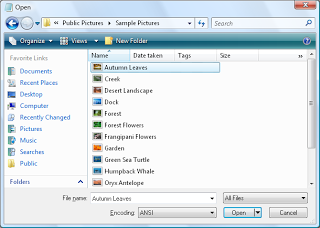

The problem with consistency is dealing with all the micro decisions that we have to make when we’re programming. When writing a file open dialog class, how do you get the name of the file the user selects? You have at least 3 choices:

The problem with consistency is dealing with all the micro decisions that we have to make when we’re programming. When writing a file open dialog class, how do you get the name of the file the user selects? You have at least 3 choices:

dialog.getFilename()dialog.get_file_name()dialog.FileName

There’s nothing wrong with any of these names or styles from a general perspective. If you write Java code, option #1 is a good choice. Option #2 is reasonable for people writing C++ code that uses the STL. But on .NET, there is no choice: you need to go with #3.

Names in .NET libraries must follow a few simple rules. Almost all names in .NET are “PascalCased” except for method arguments which are “camelCased.” Acronyms over two letters are treated as words (e.g. System.IO and System.Xml). There are also a few rules about compound words that I had to burn into my memory after I broke the rules too many times:

| Pascal | Camel | Not |

|---|---|---|

| Canceled | canceled | Cancelled |

| FileName | fileName | Filename |

| Hashtable | hashtable | HashTable |

| Id | id | ID |

| Ok | ok | OK |

| UserName | userName | Username |

(Subset of table from p.43)

The book hints at the naming process:

“In the initial design of the Framework, we had hundreds of hours of debate about the naming style. To facilitate these debates we coined a number of terms. With Anders Hejlsberg, the original designer of Turbo Pascal, and key member of the design team, it is no wonder that we chose the term PascalCasing for the casing style popularized by the Pascal programming language.” - Brad Abrams, p.38

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter how the name styles were chosen. The decision has been made. I once thought it didn’t matter about these tiny details, but it really adds up over thousands of methods. Name things however you want on other platforms: use underscores, SCREAMING_CAPS, whatever, just not in .NET.

Hurling Programmers into a Pit of Success

It’s sometimes humbling when you see people use an API that you worked hard on. Imagine that you’ve spent a week creating a class that hides all the database goo involved in getting employee information and puts it into an array. Then, to your horror, you see someone write this:

Company company = GetCompany(companyName);

for (int i = 0; i < company.Employees.Length; i++)

{

Paycheck paycheck = CreatePaycheck(company.Employees[i]);

SendPaycheck(paycheck);

}Since you decided to expose things as a mutable array, you have to make a copy before returning it. The poor guy writing this simple code is going to have terrible performance because your code made it look like getting the employees array was “cheap.” His code is doomed to 2n copies of the employee array because of your decision. The guidelines give guidance on how to avoid this problem: return a read-only collection or rename the property to a “GetEmployees” method so that programmers know the task isn’t “cheap.”

In addition to thinking about performance, you also have to keep in mind the context in which your code will be called. I’ve seen too many modern APIs that were designed by people who either didn’t think about or care about their users. Methods that have boolean parameters are usually suspect. Methods with multiple boolean parameters are downright terrible.

Compare:

Stream stream = File.Open("file.txt", true, false);with

Stream stream = File.Open("file.txt", FileMode.Open, FileAccess.Read);Can you tell what the first one does? What about the second?

When I first read the “Member Design” chapter two years ago, I vowed I would never subject users to out-of-context boolean parameters again. A benefit of this has been that I’m able to read my old code months or years later and still understand what it does when I otherwise would have long forgotten the boolean parameters of a function.

There are many other, sometimes subtle things you can do to help make users successful with your code:

- If you override .Equals on your class, you really should override .GetHashCode or your objects might do bad things when put in hashtables/dictionaries. (p.270)

- If you need a specific time of day (e.g. when to unlock a door each day), use a TimeSpan rather than a DateTime with some random date or some arbitrary number. (p.263)

- If you have an asynchronous method that invokes an event handler, make sure you do it on the proper thread (p.306). If you don’t, you might scar a novice programmer for life with threading pains.

- Don’t forget that end-users need to unit-test their code that is built using your library (p.7). This might involve making key methods virtual or factoring them out to an interface that can be swapped out with a “mock” implementation.

Nobody’s Perfect

Even when you have the best intentions, you’ll make mistakes. For example, Path.InvalidPathChars is a mistake. It’s a read-only field that is an array of characters that are invalid in filenames. Although the array reference is read-only, the array contents are not. This can lead to potential security issues if users depend on this array for safety and malicious code modifies the array contents.

Microsoft now recommends people use Path.GetInvalidPathChars() instead which returns a copy of the array instead. This is sort of ironic because it violates another type member guideline:

“DO NOT have properties that match the name of ‘Get’ methods” - p.69

This isn’t too bad since Microsoft has marked the old method as obsolete, which gives them a chance to remove it in, ten years or so. In the meantime, novice users might continue to be confused as to why there are two ways for getting invalid path characters.

Public APIs: 21st Century Sewer Systems

I often think that public APIs are like sewer systems. They’re the low-level “plumbing” that no one really cares about or notices when they’re working well. In fact, being boring is a “feature:”

I often think that public APIs are like sewer systems. They’re the low-level “plumbing” that no one really cares about or notices when they’re working well. In fact, being boring is a “feature:”

“Please don’t innovate in library design. Make the API to your library as boring as possible. You want the functionality to be interesting, not the API.” - Chris Sells, p.5

It’s easy to look at guidance like the Framework Design Guidelines and think they’re a bunch of minute details that don’t really matter and that following them will turn you into a mindless drone. Maybe I’m brainwashed, but I’ve found that having a de-facto standard on details helps me concentrate on the bigger picture: designing the functionality that users care about.

In addition to the book, there are other good resources online:

- The Framework Design Guidelines Digest

- Framework Design Guidelines session from PDC 2008

- FxCop is a tool that will automatically check your code for guideline “violations.” It was especially helpful in helping me fix Turkey Test violations.

.NET is just one framework out there. There are great lessons from other platforms as well. Google’s Chief Java Architect, Josh Bloch, has some great advice on developing good APIs, very little of it is specific to Java.

In The End…

Although it takes a lot of work to create a public API, it can be incredibly rewarding. It’s exciting to hear about people you’ve never met before successfully using an API you’ve written.

Have fun, develop great code, and go public with care.