Wetware Refactorings

While others were enjoying the final months of their college senioritis, I was worried about brain rot. It hit me that in order to be bad or at best mediocre at something, all I had to do was… nothing. From a boring job to a bad marriage, it seemed that the secret to mediocrity was to coast along and not make any adjustments or actively work to make things better. Towards graduation, I knew that I had the option of going into the workplace and just let things happen, stop actively learning, and let my brain rot. It’d take awhile for people to realize that I’d stopped caring about learning. But by then, I’d be locked into a job where it didn’t matter.

The alternative was to force myself to keep learning and accept the fact that it would never be easy. Fearful of brain rot, I decided to pick this second path. But I was on my own. Unlike school, there wouldn’t be anyone forcing me to learn new things. Even with this decision, there was a slight feeling I was part of a losing game.

Throughout my school years, the consistent message about the brain was that you were given a limited number of brain cells at birth and you had to do your best to keep all the ones you could. At best, you could hope to somehow mature the ones that remained. Popular culture promoted this message and sometimes joked about it, such as Cliff’s “Buffalo Theory” on Cheers:

“Well you see, Norm, it’s like this… A herd of buffalo can only move as fast as the slowest buffalo and when the herd is hunted, it is the slowest and weakest ones at the back that are killed first. This natural selection is good for the herd as a whole, because the general speed and health of the whole group keeps improving by the regular killing of the weakest members. In much the same way, the human brain can only operate as fast as the slowest brain cells. Now, as we know, excessive drinking of alcohol kills brain cells. But naturally, it attacks the slowest and weakest brain cells first. In this way, regular consumption of beer eliminates the weaker brain cells, making the brain a faster and more efficient machine. And that, Norm, is why you always feel smarter after a few beers.”

I kept this depressing view of brain cell scarcity until I learned about neurogenesis:

Fortunately, professor Elizabeth Gould thought otherwise. In a discovery that turned the field on its ear, she discovered neurogenesis – the continued birth of new brain cells throughout adulthood. But here’s the funny part. The reason researchers had never witnessed neurogenesis previously was because of the environment of their test subjects.

If you’re a lab animal stuck in a cage, you will never grow new neurons.

If you’re a programmer stuck in a drab cubicle, you will never grow new neurons.

On the other hand, in a rich environment with things to learn, observe, and interact with, you will grow plenty of new neurons and new connections between them.

For decades, scientists were misled because an artificial environment (sterile lab cages) created artificial data. Once again, context is key. Your working environment needs to be rich in sensory opportunities, or else it will literally cause brain damage.

Pragmatic Thinking and Learning, p.67

Neurobics

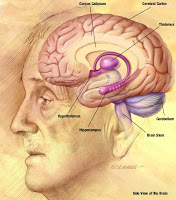

In an attempt to take advantage of this discovery, I checked out the book “Keep Your Brain Alive: 83 neurobic exercises to help prevent memory loss and increase mental fitness.” It was a bit odd for me to read since the book is targeted at people twice my age, but it highlighted the interesting concept of “neurobics” which are like neural aerobics. The book explains how neurobics take advantage of the decentralized nature of your brain:

- Involve one or more of your senses in a novel context. By blunting the sense you normally use, force yourself to rely on other senses to do an ordinary task. For instance: Get dressed for work with your eyes closed.

- Engage your attention To stand out from the background of everyday events and make your brain go into alert mode, an activity has to be unusual, fun, surprising, engage your emotions, or have meaning for you. (e.g. turn the pictures on your desk upside down)

- Break a routine activity in an unexpected, nontrivial way. Novelty just for its own sake is not highly neurobic. Routine breakers include taking a completely new route to work and shopping at a farmers market instead of a supermarket. - Keep Your Brain Alive, pp.33-34

Some of my favorite suggestions from the book include:

- Shower with your eyes closed. (p.43)

- Brushing roulette: brush your teeth with your nondominant hand. (p.44) This also works for other routine activities like using your mouse.

- The sightless start: enter and get ready to start your car with your eyes closed. (p.55)

- Take brain breaks: a walk or social lunch break can help invigorate the mind. (p.81)

- Have an ongoing chess game.

The last was the most interesting, and had me involve coworkers:

We know of one office where a chessboard was left out near the water cooler. Any employee could come to the board (preferably during a break), assess the situation, and make a move. It was an ongoing game, with no known players, and no winners or losers.

Even a novice chess player will weigh dozens of possible moves, attempt to visualize the consequences of each one, then select the move that offers some strategic advantage. This type of “Random-player” chess game doesn’t allow anyone to develop a long-term strategy. But it does require visual-spatial thinking that is different from what most of us do at work. The brief gear switching provides a break from verbal, left-brain activities and lets the “working brain” take a breather. - Keep Your Brain Alive, p.83

In my case, the chess game didn’t work out exactly like the book described, but it has been fun. I set up a small magnetic chess board on my desk and encouraged anyone to come and make a move. I thought it’d be interesting to have clear winner and loser. This posed a challenge of how to keep track of the game that had no time limit or fixed set of players. I used a business card to track of whose turn it is. When the side with the printing on it is turned up, it means that it’s black’s turn; otherwise it’s white’s turn. This “protocol” has worked out well and has allowed several coworkers to play throughout the day. As a side benefit, it’s caused me to actively work at getting better at chess.

Refactoring Your Wetware

Last week, I read through Andy Hunt’s excellent “Pragmatic Thinking & Learning: Refactor Your Wetware” that has many more pragmatic brain tips that are written from a programmer perspective. The book is centered around the Dreyfus Model of skill acquisition where learning starts at a beginner stage where you need a lot of rules to function and then transitions all the way up to an expert level where you rely heavily on intuition. Here are just a few of the many ideas presented in the book:

Last week, I read through Andy Hunt’s excellent “Pragmatic Thinking & Learning: Refactor Your Wetware” that has many more pragmatic brain tips that are written from a programmer perspective. The book is centered around the Dreyfus Model of skill acquisition where learning starts at a beginner stage where you need a lot of rules to function and then transitions all the way up to an expert level where you rely heavily on intuition. Here are just a few of the many ideas presented in the book:

Add sensory experience to engage more of your brain: continuing on the neurobics theme, Andy Hunt has some interesting ideas (pp.74-75):

- Instead of UML diagrams, try toy blocks or Lego bricks.

- Use physical CRC cards to engage your touch and spatial senses.

- Draw a picture (“not UML or an official diagram; just a picture”)

- Describe your design verbally.

- Act out your software design with coworkers.

Create a “Pragmatic Investment Plan” where you treat your skills and what you want to learn with at least as much care as you take with your finances and apply similar skills (e.g. diversify, have short and long term goals). Make sure your goals are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Boxed (SMART) (pp.154-156)

Consider starting a reading group with people in the office to help learn a skill from a book. (p.164)

Make sure you have freedom to explore ideas by having a “starter kit” infrastructure of version control, unit testing, and build automation. This gives you the safety to fail, which is often needed when learning. (p.192)

Unscaffolding: artificially make things harder than they need to be so that when you have to do it for real, it seems a lot easier (e.g. train for running by tying weights to your ankles). I like how the author claims that this is why Ruby programmers should at least spend some time working in C++ (p.206)

Develop Your Exocortex: Have a place outside your brain where you can store and organize thoughts. The author recommends a personal wiki. I personally prefer to use Google Notebook. (p.221)

Be the Query

I enjoyed the discussion in the book on changing your perspective, especially when it comes to feeling like you’re inside the system you’re creating:

Imagine yourself as an integral component of the problem you’re working on: suppose you are the database query or the packet on the network. When you get tired of waiting in line, what will you do? Who would you tell? - (p.107)

I think that this approach can help lead to a richer Object Thinking in software designs. For example, if you can picture yourself as a database query, I think you’ll have much more empathy for what’s going on. This thinking might influence your design to avoid painful table scans and favor indexes.

Another way to change your perspective is to use oblique strategies:

These questions and statements force you to draw analogies and to think more deeply about the problem. They are a great resource to draw on when you’ get stuck. - (p.108)

Some example strategies include:

- Use fewer notes

- Don’t be afraid of things because they’re easy to do.

- What wouldn’t you do?

I printed a bunch of cards with each strategy on them and keep them by my desk in a coffee mug. It’s a new addition, so I don’t have long term results, but it is fun to take one out and think of how it might relate to a problem I’m working on when I get stuck.

Keep Your Brain Cache Warm

Many brain changing ideas require you to focus. This is hard to do when our jobs often require us to multitask or our culture encourages us to check email frequently in order to respond quickly and look good among our peers. There are dangers to this:

Scientists agree that trying to focus on several things at once means you’ll do poorly at each of them.

And if that wasn’t bad enough, a controversial study done in the United Kingdom noted that if you constantly interrupt your task to check email or respond to an IM text message, your effective IQ drops ten points.

By comparison, smoking a marijuana joint drops your IQ a mere four points. - Pragmatic Thinking and Learning, p.228

This is really hard to overcome. Since reading this, I’ve tried to avoid checking Outlook more than once an hour. After each check, I shut it down to prevent the distraction. I’ve found that it’s helpful to actually shut it down; otherwise it’s too tempting to ALT+TAB to it or get lured in by a notification message.

If you replace “phone” with “email”, you can see that Peopleware described over two decades ago why most people are working far below their potential of being in a state of “flow” where you actually get stuff done:

If the average incoming [email] takes five minutes and your reimmersion period is fifteen minutes, the total cost of that [email] in flow time (work time) lost is twenty minutes. A dozen [emails] use up half a day. A dozen other interruptions and the rest of the work day is gone. This is what guarantees, “You never get anything done around here between 9 and 5.” - Peopleware 2nd edition, p.63

Therefore, for the sake of your sanity and focus, be careful before flushing your brain cache by doing a context switch. The time saved can be used for more creative thinking and getting things done.

Is this All a Bunch of Hooey?

I admit that some of these ideas sound silly. I haven’t yet worked up the courage to bring Legos to a design meeting yet, but I can see how it would help use a different neural pathway and activate more gray matter. Surely that couldn’t hurt, right? It’d probably bring a new perspective and overcome a road block. This is probably why some of the most creative companies encourage playful behavior at work. This might be seen as a horrible waste of time to traditional management (and shareholders for that matter), but it’s much more likely to use more of your brain which in turn might create better solutions.

One alternative to all of this is to just coast along and not take thinking and learning into your own hands. Left on their own, your company is likely to put you through a sheep dip using a “training course” in an artificial environment that will easily wear off just like a farmer might dunk his sheep into a chemical bath to get rid of parasites which will also wear off and need to be repeated.

One alternative to all of this is to just coast along and not take thinking and learning into your own hands. Left on their own, your company is likely to put you through a sheep dip using a “training course” in an artificial environment that will easily wear off just like a farmer might dunk his sheep into a chemical bath to get rid of parasites which will also wear off and need to be repeated.

While sometimes uncomfortable at first, I’ve enjoyed incorporating some “wetware refactoring” into my daily life as a way to overcome brain rot and aid learning and thinking. It sure beats a sheep dip.

What do you do? Do you have specific wetware refactorings that you do? I’d love to hear them; the “crazier” they are the more likely they’ll probably activate different neural pathways and probably lead to a better result. Let me know in the comments.