Life, Death, and Splitting Secrets

(Summary: I created a program to help back up important data like your master password in case something happens to you. By splitting your secret into pieces, it provides a circuit breaker against a single point of failure. I’m giving it away as a free open source program with the hope that others might find it useful in addressing this aspect of our lives. Feel free to use the program and follow along with just the screenshots below or read all sections of this post if you want more context.)

Background

I just couldn’t do it.

My grandma died at this time last year from a stroke. She was a great woman. I still miss her. In that emotional last week, I was reminded of great memories with her and the fragility of life. I was also reminded about important documents that I still didn’t have.

My grandma died at this time last year from a stroke. She was a great woman. I still miss her. In that emotional last week, I was reminded of great memories with her and the fragility of life. I was also reminded about important documents that I still didn’t have.

When something happens to you, be it death or incapacitation, there are some important steps that need to occur that can be greatly assisted by legal documents. For example:

- An advance health care directive (aka “Living Will”) specifies what actions should (or shouldn’t) be taken with regards to your healthcare if you’re no longer able to make decisions for yourself.

- A durable power of attorney allows you to designate someone to legally act as you if you become incapacitated.

- A last will and testament allows you to legally assign caregivers for minor children as well as designate where you’d like your possessions to go.

My grandma had these and it helped reduce stress and anxiety in this difficult time. We knew what she would have wanted and these documents helped legally enforce that.

I had assumed that these documents were expensive and time-consuming to create. Furthermore, as a guy in my 20’s, death still seems like a distant rumor. As a Christian, I’m not overly concerned about death itself, but my grandma’s death reminded me that these documents are not really for me, but rather the people I’d leave behind. I knew that if something happened to me, I’d potentially be leaving behind a mess, and that concern of irresponsibility compelled me to investigate what I could do.

It turns out that creating these documents is essentially a matter of filling out a form template. I bought a program that made it about as easy as preparing taxes online. In most cases, you just need disinterested third parties, such as friends or coworkers, to witness you signing them to make them fully legal. At most, you might have to get them notarized or filed in your county for a small fee.

One of the steps involved in filling out the “Information for Caregivers and Survivors” document is to list “Secured Places and Passwords.” It’s a helpful section that your executor can turn to if something happened to you in order to do things like unlock your cell phone or access your online accounts. Sure, your survivors might be able use legal force to get access without it, but only after months of sending official documentation. That’s a lot of hassle to put someone through. Also, it’s very likely that a lot of important things will be missed and no one would ever know they existed.

It’s probably rational to just write your passwords down and put them in a safe which your executor knows the location of and can access in a timely matter. Alternatively, you could pay for an attorney or a third-party service and leave your password list with them. However, this seemed like it would cause a maintenance problem, especially as I might add or update my passwords frequently. These options would also force me to trust someone I haven’t known for a long time. Most importantly, the thought of writing down my passwords on a piece of paper, even if it was in a relatively safe place, went against every fiber of my security being.

I just couldn’t do it.

DISCLAIMER: The above simple approaches are probably fine and have worked for a lot of people over the years. If you’re comfortable with these basic approaches, by all means use them and ignore this post. These simpler approaches have less moving parts and are easy to understand. However, if you want a little more security, or need to liven up this process with a little spy novel-esque fun, read on.

The Modern Password & Encryption Problem

As an online citizen, you don’t want to be that person. You know, the one whose password was so easy to guess that his email account was broken into and who “wrote” to you saying that he decided to go to Europe on a whim this past weekend but now needs you to wire him money right now and he’ll explain everything later: that guy.

You’ve learned that passwords like “thunder”, “thunder56”, and even “L0u|>Thund3r” are terrible because they’re easily guessed. You now know that the most important aspect of a password is its length combined with basic padding and character variation such as “/* Thunder is coming! */”, “I hear thunder!”, or “[email protected]”.

In fact, you’re probably clever enough that you don’t create or remember most of your passwords anymore. You use a password manager like LastPass or KeePass to automatically generate and store unique and completely random passwords for all of your accounts. This has simplified your life so that you only have to remember your “master password” that will get you into where you keep all the rest of your usernames and passwords.

You also understand that your email account credentials are a “skeleton key” for almost everything else due to the widespread use of simple password reset emails. For this very reason, you probably realize that it’s critical to protect your email login with “two-factor” authentication. That is, your email account should at least be protected by:

- Something you know (your password) and

- Something you have (your cellphone), that creates or receives a one-time use code when you want to login.

On top of all of this, you try your best to follow the trusty advice that your passwords should be ones that nobody could guess and you never ever write them down.

But what if something happens to you? If you’ve done everything “right,” then your master password and all your second factor details go with you.

And then there are your encrypted files. Maybe you’re keeping a private journal for your children to read when they grow up. Perhaps you’re living in some spy novel life where you’re worried that people will take you out to prevent something you know from being discovered. Wherever you fall on the spectrum, what do you do with such encrypted data?

Modern encryption is a bit scary because it’s so good. If you use a decent encryption program with a good password/key, then it’s very likely that no one, not even a major government, could decrypt the file even after hundreds of years. Encryption is great for keeping prying eyes out, but it could sadden survivors that you want to have access to your data. The thought of something being lost forever might make you almost yearn for the days when you just put everything into a good safe that’s rated by how many minutes it might slow somebody down.

On a much lighter note, the “something” that happens to you doesn’t have to be so grim. Maybe you had a really relaxing three week vacation and now you can’t remember the exact keyboard combination of your password. Given that our brains have to recreate memories each time you recall something, it’s possible that you could stress yourself out so much trying to remember your password that you effectively “forget” it. What do you do then?

When you put all your eggs into a password manager basket, you really want to watch that basket. Fortunately, creating a basic plan isn’t that hard.

A Proposed Solution

Let’s borrow an ancient yet incredibly useful idea: if it’s really important to get your facts right about something, be sure to have at least two or three witnesses. This is especially true concerning matters of life and death but it also comes up when protecting really valuable things.

By the 20th century, this “two-man rule” was implemented in hardware to protect nuclear missiles from being launched by a lone rogue person without proper authorization. The main vault at Fort Knox is locked by multiple combinations such that no single person is entrusted with all of them. On the Internet, the master key for protecting the new secure domain name system (DNSSEC) is split between among 7 people from 6 different countries such that at least 5 people are needed to reconstruct it in the event of an Internet catastrophe.

If this idea is good enough for protecting nuclear weapons, the Fort Knox vault, and one of the most critical security aspects on the Internet, it’s probably good enough for your password list. Besides, it can make a somewhat uncomfortable process a little more fun.

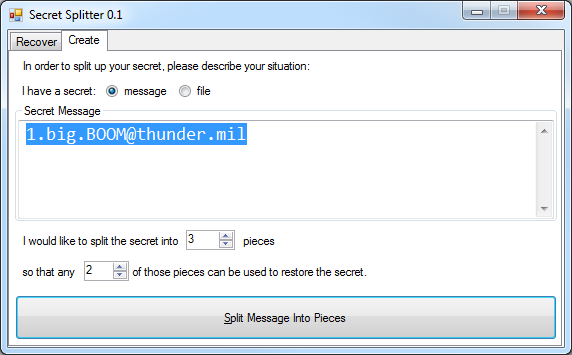

Let’s start with a simple example. Let’s say that your master password is “[email protected]”. You could just write it out on a piece of paper and then use scissors to cut it up. This would work if you wanted to split it among 2 people, but it has some notable downsides:

- It doesn’t work if you want redundancy (i.e. any 2 of 3 people being able to reconstruct it)

- Each piece would tell you something about the password and thus has value on its own. Ideally, we’d like the pieces to be worthless unless a threshold of people came together.

- It doesn’t really work for more complicated scenarios like requiring 5 of 7 people.

Fortunately, some clever math can fix these issues and give you this ability for free. I created a program called SecretSplitter to automate all of this to hopefully make the whole process painless.

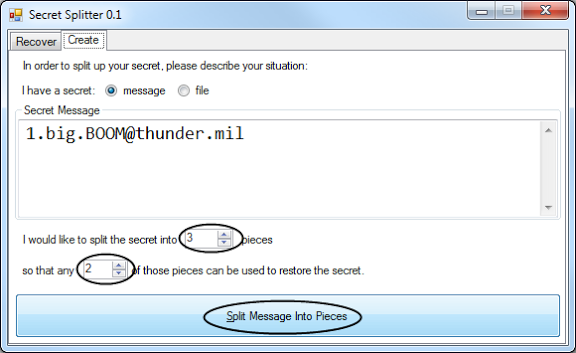

Let’s say you want to require at least 2 witnesses to agree that something happened to you before your secret is available. You also want to build in redundancy such that any pair of people can find out your password. For this scenario, you keep the can use the default settings and press the “split” button:

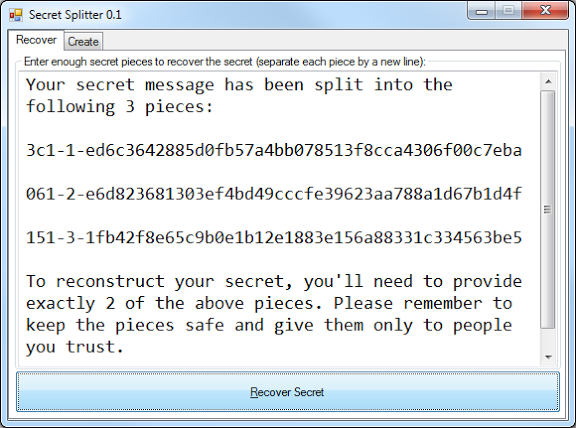

You’ll get this list of split pieces:

Notice that each piece is twice as long as your original message (about twice the size of a package tracking number). This is by design.

Now comes the hard part: you have to select three people you trust. You should have high confidence in anyone you’d entrust with a secret piece. It’s easy to get caught up in gee-whiz cryptography and miss fundamentals: you ultimately have to trust something, especially with important matters. SecretSplitter provides a trust circuit breaker just in case (because even well-meaning people can lose important things). The splitting process adds a bit of complexity, but so do real circuit breakers. If you trust no one, then you can’t have anyone help you if something happens.

For demonstration purposes, let’s say you trust 3 people.

You now have to distribute these secret pieces. You could do all sorts of clever things like send letters to people that will be delivered far in the future or read them over the phone. However, distributing them in person is a pretty good option:

It can make the upcoming holiday table discussions even more fun:

Let’s pretend that something happened to you. Two of the three family members that you gave pieces to would come together and agree that “something” indeed has happened to you. What happens now?

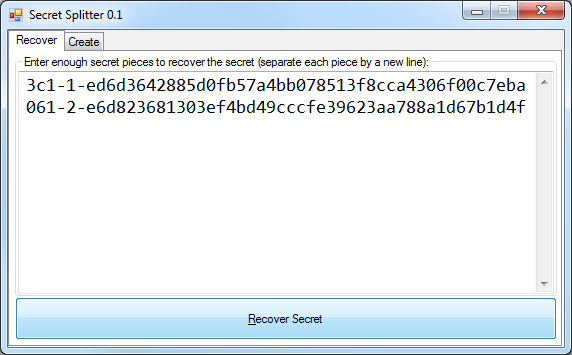

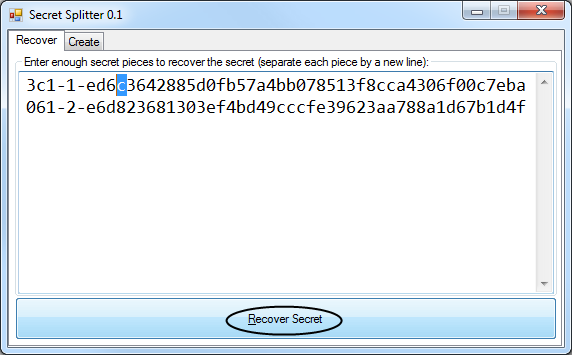

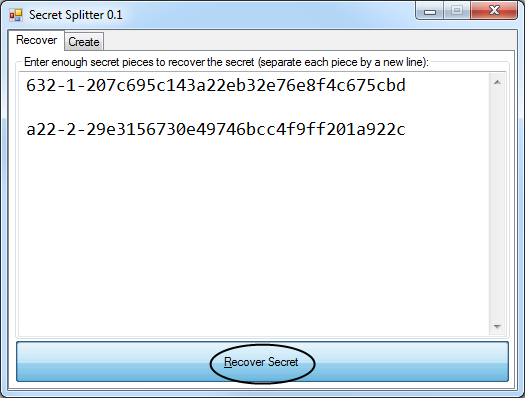

Well, either you included a note with each secret piece or you emailed them previously with instructions that they’d just need to download and run this small program. The pair comes together at a laptop and they each type their piece in quickly and then press “Recover”:

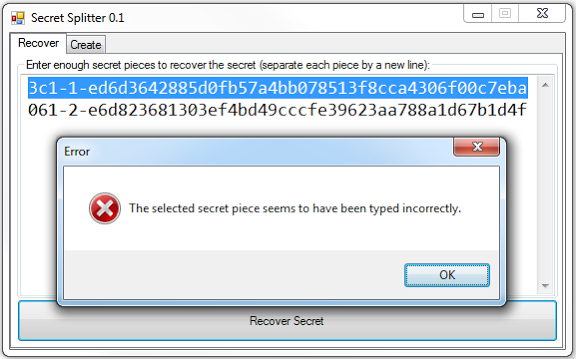

Oops… they typed so quickly that they mixed up one of the digits. It told us where to look:

They fix the typo and press recover again:

And immediately they see:

Password recovered! They could now use this master password to log into your password manager where you’ve stored further details.

This “message” approach is useful if you have a small amount of data such as a password that you could write on a piece of paper. One downside is that each piece is twice the size of the text message. If your message becomes much larger then it will no longer be feasible to type it in manually.

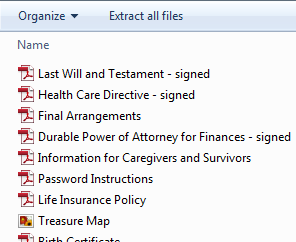

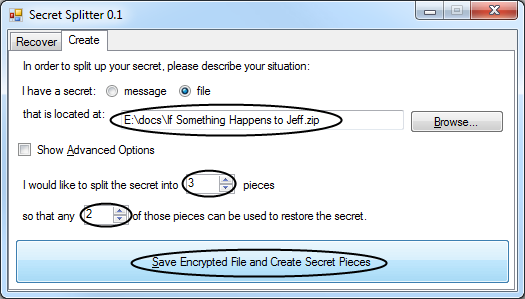

One alternative approach is to bundle together all of your important files into a zip file:

To split this file, you’d click the “Create” tab and then find the file, set the number of shares and click “Save”:

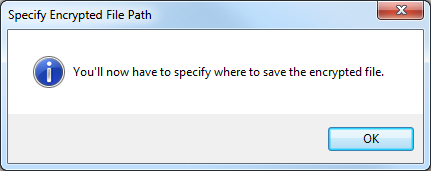

You’ll then be told:

And then you pick where to save the encrypted file:

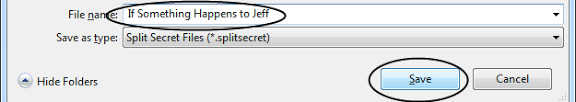

Finally, you’ll see this screen:

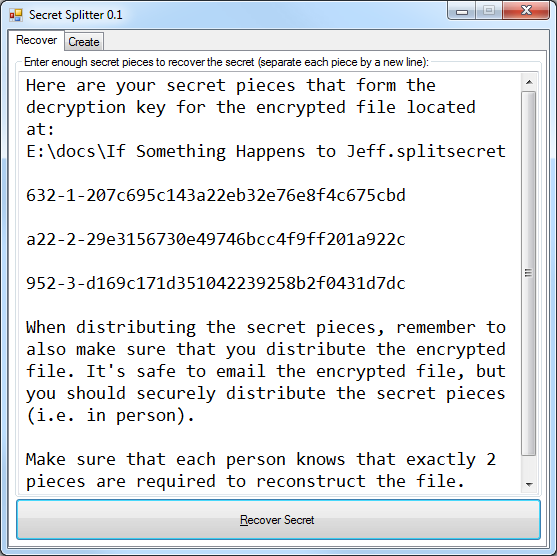

This creates a slightly more complicated scenario because you now have 2 things to share: the secret pieces and the encrypted file with all your data. The encrypted file doesn’t have to be secret at all. You can safely email it to people that have a secret piece:

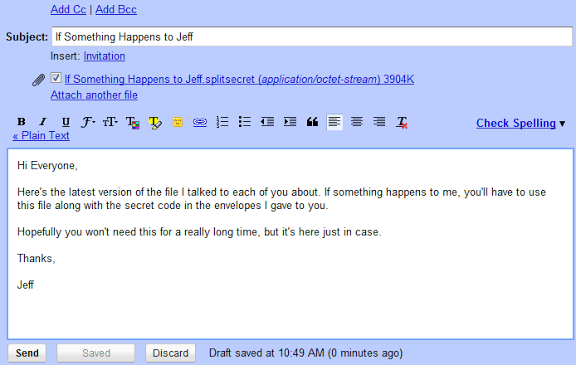

Now, if something happens to you, they’d run the program, and type in two shares and press “Recover”:

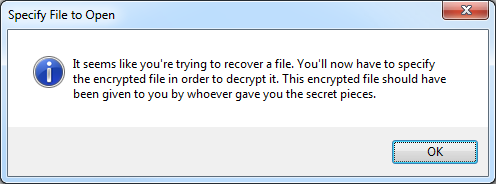

It’ll then tell them:

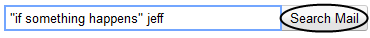

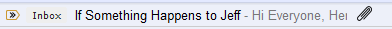

They’d then go to their email and search for the email from you that includes your encrypted file:

Then they’d find the single message (or the latest one if you sent out updates) and download your encrypted attachment:

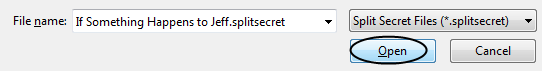

They’d then go back to the program to open it up:

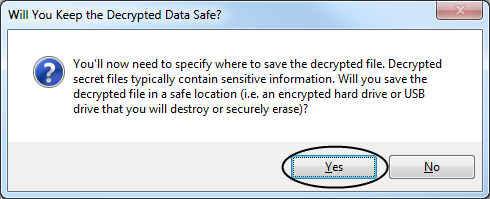

and then they’d see a message to be careful where they saved it:

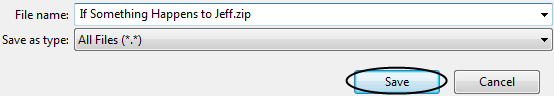

and then they’d save it:

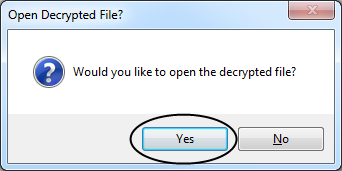

They’d then be asked if they want to open the decrypted file, which they’d say “Yes”:

Now they can see everything:

It might sound complicated, but if you’re familiar with the process, it might only take a minute. If you’re not tech savvy and have never done it before and type slowly, it might take 30 minutes. In either case, it’s faster than having to drive to your home and search around for a folder and it contains everything you wanted people to know (especially when things are time sensitive).

That’s it! Your master password and important data are now backed up. The risk is distributed: if any one piece is compromised (i.e. gets lost or misplaced), you can have everyone else destroy their secret piece and nothing will be leaked. Also, the program has an advance feature that lets you save the file encryption key. This feature allows you to send out updated encrypted files that can be decrypted with the pieces you’ve already established in person.

SecretSplitter implements a “(t,n) threshold cryptosystem” which can be thought of as a mathematical generalization of the physical two-man rule. The idea is that you split up a secret into pieces (called “shares”) and require at least a threshold of “t” shares to be present in order to recover the secret. If you have less than “t” shares, you gain no information about the secret. Whatever threshold you use, it’s really important that each “shareholder” know the threshold number of shares.

You can be quite creative in setting the threshold and distributing shares. For example, you can trust your spouse more by giving her more shares than anyone else. The key idea is that a share is an atomic unit of trust. You can give more than one unit of trust to a person, but you can never give less.

Another important practical concern is that you should consider adding redundancy to any threshold system. This is easily achieved by creating more shares than the threshold number. The reason is that if you’re going out of your way to use a threshold system, then you probably want to make sure you have a backup plan in case one or more of the shares are unavailable.

IMPORTANT LEGAL NOTE: It’s tempting to keep everything, including the important directives and your will in only electronic form (even when they’re signed). Unfortunately, most states require the original signed documents to be considered legal and most courts will not accept a copy. For this reason, you should still have the paper originals somewhere such as a fireproof safe. However, be careful where you put the originals: although it might sound convenient to put them in a bank safety deposit box, there’s usually a rather long waiting period before a before a bank can legally provide access to your box to a survivor, so don’t put any time sensitive items there. My recommendation at the current time would be to include copies of the signed originals in your encrypted file and also include detailed instructions on where the originals are located and how to access them.

How It Works

Given the sensitive nature of the data being protected, I wanted to make sure I understood every part of the mathematics involved and literally every bit of the encrypted file. You’re more than welcome to just use the program without fully understanding the details, but I encourage people to verify my math and code if you’re able and curious.

To get started, recall that computers work with bits: 1’s and 0’s that can represent anything. For example, the most popular way of encoding text will encode “thunder” in binary as

01110100 01101000 01110101 01101110 01100100 01100101 01110010

We can write this more efficiently using hexadecimal notation as: 74 68 75 6E 64 65 72. We can also treat this entire sequence of bits as a single 55 bit number whose decimal representation just happens to be 32,765,950,870,971,762. In fact, any piece of data can be converted to a single number.

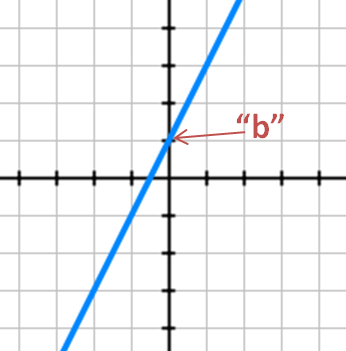

Now that we have a single number, let’s go back to your algebra class and remember the equation for a line: y=mx+b.

In this equation, “b” is the “y-intercept”, which is where the line crosses the y-axis. The “m” value is the slope and represents how steep the line is (i.e. its “grade” if it were a hill).

This is all the core math you need to understand splitting secrets. In our particular case, our secret message is always represented by the y-intercept (i.e. “b” in y=mx+b). We want to create a line that will go through this point. Recall that a line could go through this point at any angle. The slope (i.e. “m” in y=mx+b) will direct us where it goes. For things to work securely, the slope must be a random number.

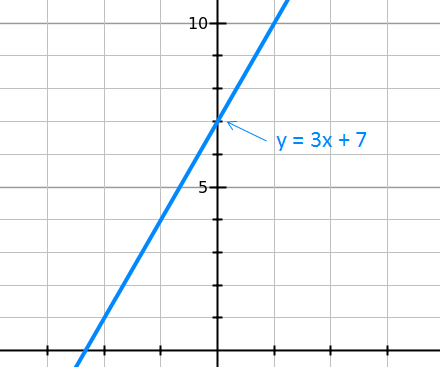

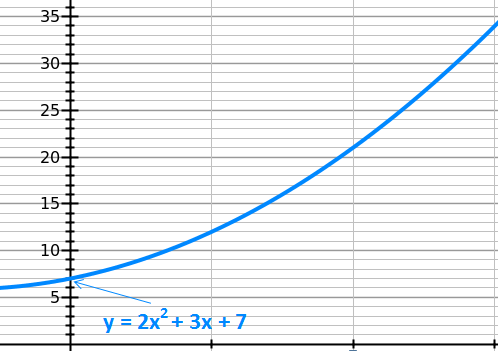

Although we use large numbers in practice for security reasons, let’s keep it simple here. Let’s say our secret number is “7” and our random slope is “3.” These choices generate this line:

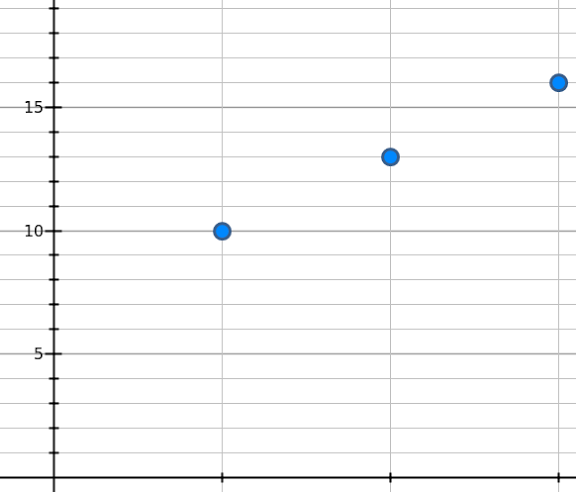

With this equation, we can generate an infinite number of points on the line. For example, we can pick the first three points: (1, 10), (2, 13), and (3, 16):

You can see that if you had any two of these points, you could find the y-intercept.

It’s critical to realize that having just one of these points gives us no useful information about the line. However, having any other point on the line would allow us to use a ruler and draw a straight line to the y-intercept and thus reveal the secret (we could also work it out algebraically). Each point represents a secret piece or “share” and has a unique “x” and “y” value.

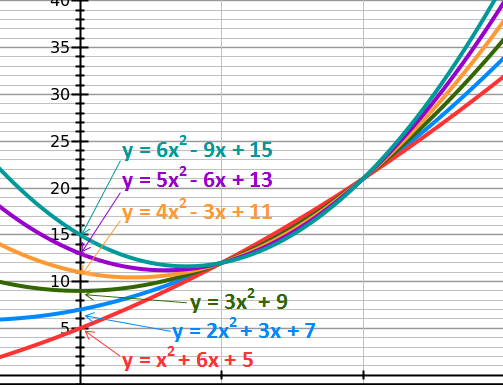

The mathematically fascinating part about this idea is that a line is just a simple polynomial (curve) and this technique works for polynomials of arbitrarily large degrees. For example, a second degree polynomial is a parabola that requires 3 unique points to completely define it (one more than a line). Its equation is of the form y=ax^2 + bx + c. In our case “c” is the y-intercept and “a” and “b” are random as in y = 2x^2 + 3x + 7:

Given this equation, we can generate as many “shares” as we’d like: (1,12), (2,21), (3,34), (4,51), etc.

Keep in mind that a parabola requires three points to uniquely define it. If you just had two points, as in (1,12) and (2,21), you could create an infinite number of parabolas going through these points and thus have infinite choices for what the y-intercept (i.e. your secret) could be:

However, a third point will define the parabola and its y-intercept exactly:

You’ve just learned that splitting a secret that requires three people is just a matter of creating a parabola. Requiring more people is just a matter of creating a higher-degree polynomial such as a cubic or quartic polynomial. If you understand this basic idea, the rest is just details:

- Instead of using numbers, we translate the data to a big polynomial with binary coefficients.

- Instead of using middle school algebra, we use a “finite field.” This helps keep results about the same size as the input and adds some security.

Don’t be intimidated by these changes. The core ideas are the same as the basic case. The only noticeable difference is that you have to think of operations like multiplication and division in a more abstract way. For details, check out my source code’s use of Horner’s scheme for evaluating polynomials, peasant multiplication, irreducible polynomials with the fewest terms, Lagrange polynomial interpolation to find the y-intercept, and using Euclidean inverses for division.

Again, it probably sounds more complicated than it really is. At its core, it’s simple. This technique is formally known as a Shamir Secret Sharing Scheme and it was discovered in the 1970’s.

I didn’t want to invent anything new unless I felt I absolutely had to. There was already a good tool called “ssss-split” that generates shares similar to how I wanted. This program adds a special twist by scrambling the resulting y-intercept point and therefore adds an extra layer of protection. Since this program was already the de-facto standard, I wanted to be fully compatible with it. To make sure I was compatible, I had to copy its method of “diffusing” (i.e. scrambling) the bits using the public domain XTEA algorithm. However, to ensure complete fidelity, I had to look at the source code. The only problem was that it was originally released under the GNU Public License (GPL) and it used a GPL library for working with large numbers. My goal was to make my implementation as open as I could, so I asked the author if I could look at his code to derive my own implementation that I’d release under the more permissive MIT license and he graciously allowed me to do this.

To prove the compatibility, you can use the ssss-split demo page and paste the results into SecretSplitter and it’ll work just fine. In addition, I created command line programs from scratch that are fully compatible with ssss-split and ssss-combine.

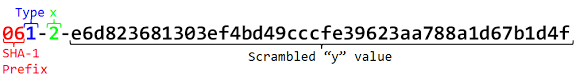

After some basic usability testing, I decided to make one small adjustment. The “ssss-split” command allows you to attach a prefix that it ignores. I wanted to add a special prefix that would tell what type of share it was (i.e. a message or a file) as well as a simple checksum because with all those digits it’s easy to mistype one.

Now, you can understand all the pieces of the long share:

In theory, you could “encrypt” a large file directly using this technique. In practice, it doesn’t work well because each share would be huge and not something you’d be able to write down by hand or say over the phone, even using the phonetic alphabet.

For lots of data, we use a hybrid approach: encrypt the file using standard file encryption with a random key and then split the small “key” into pieces.

For file encryption, I again didn’t want to invent anything new. I decided to use the OpenPGP Message Format, the same format used by PGP and GNU Privacy Guard (GPG). I didn’t want to have to worry about licensing restrictions or including a third-party library, so I wrote my own implementation from scratch that did exactly what I wanted. I read RFC4880 and started sketching out what I needed to do. A few bug fixes later and I had a working implementation that was able to interoperate with GPG. To simplify my implementation, I only support a limited subset of features:

- I always use AES with a 256-bit key for encryption, even if users select a smaller effective key size. This means that users can pick any size key they want and thus balance security and share length. I picked AES because it’s strong and understandable with stick figures.

- The actual file encryption key is always a hashed, salted, and stretched version of the reconstructed shares text.

- The encrypted file has an integrity protection packet to detect if the file has been modified and ensure it was decrypted correctly.

Since I used common formats, you can verify the correctness of the generated files using a Linux shell. You can also create files using the shell and have them interoperate with SecretSplitter. I included a sample of how to do this with the source code.

Help Wanted / Future Possibilities

SecretSplitter still looks and feels like a prototype. There are lots of possible improvements that could be made:

- Secret splitting is a relatively complicated idea. In Cryptography Engineering, the authors write “secret sharing schemes are rarely used because they are too complex. They are complex to implement, but more importantly, they are complex to administrate and operate.”

Although I tried to simplify the user experience for broad use, it could still use some user experience enhancements to simplify it further.

2. I wrote it in C# for the .net platform because that is what I’m most familiar with (and it has some built-in powerful primitives like BigIntegers, AES, and hash functions). I suspect that an HTML5 version using JavaScript, a nice interface, and coming from a trusted domain would get much broader usage. In addition, since this is a problem that affects everyone, having great internationalization support would be a nice touch. It also would be nice to have a polished look with a good logo and other graphics.

3. You could use more elaborate secret sharing schemes than what I implemented in SecretSplitter. I considered these, but ultimately wanted to use a technique that was already compatible with widely deployed tools. I also considered enhancing shares with two-factor support or using existing public key infrastructure, but decided that added too much complexity. Perhaps it’s possible to incorporate these in a good design.

4. It’d be neat if this scheme or something similar to it was integrated into LastPass and KeyPass as a core feature.

5. Obviously the shares themselves are long. I tried making them shorter but the downsides outweighed the upsides. Perhaps it could be better. Also, a compelling graphically designed share card might make it more fun for broader use. The long length is somewhat of a safety mechanism that prevents people from memorizing with a quick glance. Also, it discourages overhasty use much like freezing a credit card.

6. I kept the codes in a format that would be easy to write as well as read over the phone. I used a simple character set that avoids ambiguities like “O” vs “0”. One additional strategy could be to embed the share as a QR code or something similar. I didn’t pursue this approach in favor of simplicity, but this could be an option.

7. Really paranoid people might want to back up their encrypted file to paper. This is possible, but I’m not sure if it should belong inside the program itself.

8. It’d be good to have suggestions on how to exchange shares or perhaps borrow ideas from PGP key signing parties. I suspect that if secret splitting were to become popular, then “web of trust” scenarios would naturally occur (i.e. “I’ll hold your secret share if you hold mine”).

9. It’d be fun to compile a list of non-obvious uses for SecretSplitter to share with others. For example, it could make for interesting scavenger hunt clues.

If you’d like to donate your time to any of the above ideas, I’d encourage you to just give it a go. You don’t have to ask for my permission but it would be nice if you posted your results somewhere or left a comment to this post. You can use my code for whatever purpose you’d like. My only hope is that you might get some benefit out of it.

Conclusion

SecretSplitter is just a tool that gives another option for backing up very sensitive information by splitting it up into pieces. It’s not a full solution, only a tool. By relying on people I trust instead of a third-party company, it helped me remove one excuse I had for not preparing somewhat unpleasant but important documents that we should all probably have. I still don’t have this all figured out, but writing SecretSplitter help me get started.

If you’re young, don’t have any minor children, and don’t care at all what happens to your stuff, then you could run some mental actuarial model and convince yourself that the probability of you or your survivors needing these documents or password recovery procedure anytime soon is low, but you’re not given any guarantees.

At the very least, it’s a good idea to make sure all of your financial assets and life insurance policies have a named beneficiary and at perhaps at least one alternate. You can also declare things like organ donor preferences on your driver’s license instead of making declarations in other documents. It’s also a good idea to have an “ICE” entry in your cell phone. However, going the extra step and making very basic final documents doesn’t require that much more work. Besides, once you have baseline documents, keeping them fresh is just a matter of occasional updates due to life events.

The increasing digitization of our lives means that more personal things will only be stored digitally. From our journals to email to videos to health records, all of this will eventually only exist digitally and likely hidden behind passwords. This future needs some safety net for backing up sensitive things in a safe and accessible way.

Everything doesn’t need to be backed up. There are also lots of files, usernames and passwords that don’t really matter. Don’t include those. SecretSplitter was built with the assumption that everything that really mattered could be stored in a file small enough to email to others. This helps focus and pare down to what really matters.

It’s also good to have a healthy dose of common sense. Instead of holding out a secret until after your death, maybe you should get that resolved today. You’ll probably live better. My general view is that these final “secrets” should be mostly boring by just containing account details and credentials.

Finally, on a more personal level, I think it’s healthy to be reminded about our own mortality at least once every year or so. It’s a helpful reminder of how much a gift every day is and helps focus what we do and not worry about things that don’t matter.

If a little bit of fancy math can help you sleep better at night, well then, I’d consider it a success.

Special thanks to B. Poettering for creating the original ssss program and allowing me to clone its format.