Using Obscure Windows COM APIs in .NET

Most native Windows APIs are simple to call from .NET. For example, if you need to do something special when showing a window, you can use the ShowWindow API using Platform Invocation Services (P/Invoke) like this:

[DllImport("user32.dll")]

static extern bool ShowWindow(IntPtr hWnd, int nCmdShow);When you call this function, here’s roughly what happens:

- The CLR calls LoadLibrary on the file (e.g. “user32.dll”)

- The CLR then calls GetProcAddress on the function name (e.g. “ShowWindow”) to get the address of where the function is located.

For the most part, it just magically works. If we had used a function like “MessageBox”, the CLR would notice that it doesn’t exist and would then pick between the ANSI version (e.g. “MessageBoxA”) or the Unicode version (e.g. “MessageBoxW”).

With the address in hand, it’s easy to jump to it and you’re all set. Simple and easy.

I was expecting a simple API like this when I was investigating how to register my program as the default handler for “.wav” files on Vista. In the pre-Vista days, most programs would write directly into a registry key for the file extension (e.g. “HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\.wav”) and move on. Problems come when your program wants to register itself as a handler for a “popular” extension like .MP3 or .HTM. Some programs go into an all out arms race with other programs in a fight of wills to make sure they keep the extension.

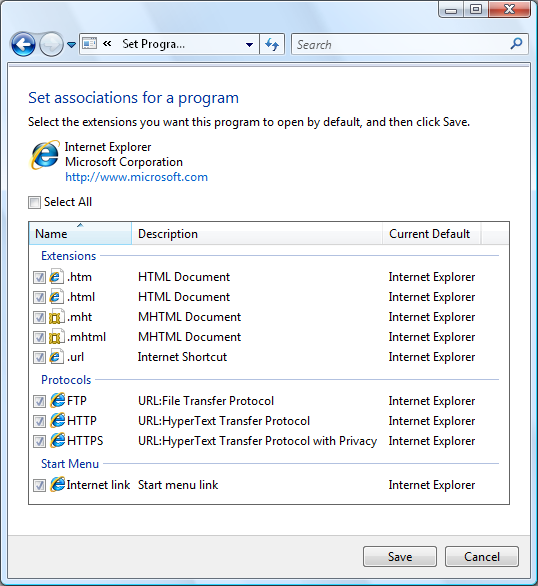

In Windows Vista and later, Microsoft wants us to use the new “Default Programs” feature. The idea is that you register what file extensions your program supports in the registry and then a nice UI allows people to easily pick which of those extensions they want to associate with your program. Digging around the documentation led me to discover that the bulk of the functionality was exposed via the IApplicationAssociationRegistration COM interface.

Ah, COM.

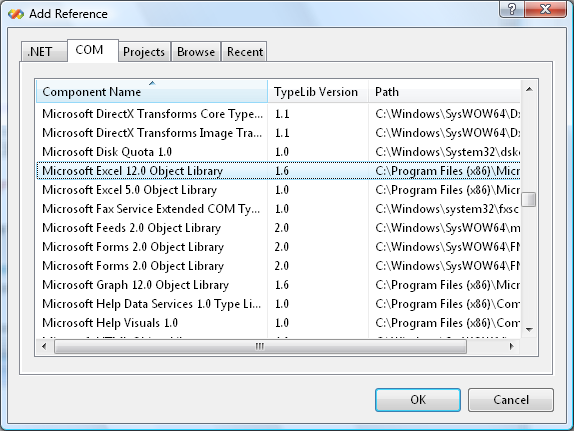

Over the years, I’ve tried to keep my distance from it. This irrational fear came from wizards that “next, next, finish”‘d your way into thousands of lines of inscrutable code. It took me years of passing glances to finally understand its basics. Even then, when I needed to use it from .NET, I’d right click on my project references and click “Add Reference”:

I’d pick the library I needed and then somehow I could use the types as if they were .NET objects. I didn’t ask further questions and moved on.

Unfortunately, IApplicationAssociationRegistration was nowhere to be found on the “Add Reference” list since it doesn’t seem to have a registered type library associated with it. Using my basic COM knowledge, I knew that if I wanted to use it I would need to know the interface identifier (IID) as well as a class identifier (CLSID) that pointed to a concrete implementation.

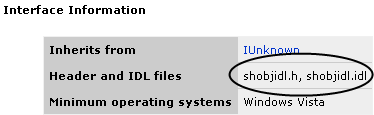

Following the MSDN documentation, I knew I’d probably find success in shobjidl.idl:

Sure enough, shobjidl.idl was sitting in my “C:\Program Files\Microsoft SDKs\Windows\v6.1\Include” directory and had this interface definition:

[

object,

uuid(4e530b0a-e611-4c77-a3ac-9031d022281b),

pointer_default(unique),

helpstring("Protocol URL and Extension File Application")

]

interface IApplicationAssociationRegistration : IUnknown

{

HRESULT QueryCurrentDefault(

[in, string] LPCWSTR pszQuery,

[in] ASSOCIATIONTYPE atQueryType,

[in] ASSOCIATIONLEVEL alQueryLevel,

[out, string] LPWSTR* ppszAssociation);

...

}A little further down was the declaration for the concrete class (coclass) and its associated class id (CLSID):

// CLSID_ApplicationAssociationRegistration

[ uuid(591209c7-767b-42b2-9fba-44ee4615f2c7) ] coclass ApplicationAssociationRegistration

{

interface IApplicationAssociationRegistration;

}In the IDL, we also see the definitions for the enums that the functions use:

typedef [v1_enum] enum tagASSOCIATIONLEVEL

{

AL_MACHINE,

AL_EFFECTIVE,

AL_USER,

} ASSOCIATIONLEVEL;

typedef [v1_enum] enum tagASSOCIATIONTYPE

{

AT_FILEEXTENSION,

AT_URLPROTOCOL,

AT_STARTMENUCLIENT,

AT_MIMETYPE,

} ASSOCIATIONTYPE;Getting this to work in .NET was surprisingly easy. The basic idea is that the CLR has to have just enough information to find the types:

- The “ComImportAttribute” is almost as simple to use as DllImportAttribute. In addition, you need to use the GuidAttribute to specify the gigantic GUIDs.

- You use the “InterfaceTypeAttribute” to specify the basic interface(s) that the interface you’re importing uses. In COM, all interfaces derive from IUnknown. If the interface supports scripting then it implements IDispatch. If you provide a speedy C++ way of accessing your interface (e.g. vtable definition) and the scripting IDispatch interface, you’ve got a “dual” interface.

- You need to translate the parameter types to their .NET equivalents. This is an incredibly mechanical process that’s straightforward. If there is a chance that the underlying bits are different between COM and .NET (e.g. they’re not blittable) then you need to use the MarshalAsAttribute to tell the CLR how to convert the types as necessary.

- You need to remember that COM handles errors by returning HRESULTs instead of natively using exceptions like .NET uses. By default, the CLR will make the last parameter that is an OUT parameter in the IDL to be the return value (it helps if it’s marked by “retval”). Therefore, you can act as if the function really returns its last parameter and the CLR will automatically check the HRESULT and throw a corresponding .NET exception as needed.

- Optionally, and perhaps most controversially, you’re free de-Hungarianize the parameter names and PascalCase the enum names to make them much more friendly looking to people in .NET. It’s optional since it might confuse people that use MSDN documentation and expecting the original names.

In a minute or so, I translated the definitions and gladly got rid of the Hungarian prefixes by converting parameter names of “pszQuery” to just “query.” I also converted all the enums and removed their unnecessary prefixes. The end result was this:

[ComImport]

[Guid("4e530b0a-e611-4c77-a3ac-9031d022281b")]

[InterfaceType(ComInterfaceType.InterfaceIsIUnknown)]

internal interface IApplicationAssociationRegistration

{

[return: MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPWStr)]

string QueryCurrentDefault( [MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPWStr)] string query,

AssociationType queryType,

AssociationLevel queryLevel);

[return: MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.Bool)]

bool QueryAppIsDefault([MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPWStr)] string query,

AssociationType queryType,

AssociationLevel queryLevel,

[MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPWStr)] string appRegistryName);

[return: MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.Bool)]

bool QueryAppIsDefaultAll(AssociationLevel queryLevel,

[MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPWStr)] string appRegistryName);

void SetAppAsDefault([MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPWStr)] string appRegistryName,

[MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPWStr)] string set,

AssociationType setType);

void SetAppAsDefaultAll([MarshalAs(UnmanagedType.LPWStr)] string appRegistryName);

void ClearUserAssociations();

}Importing the concrete class that implements the interface was just a matter of specifying its CLSID:

[ComImport]

[Guid("591209c7-767b-42b2-9fba-44ee4615f2c7")]

internal class ApplicationAssociationRegistration

{

// coclass is implemented by the runtime callable wrapper

}With all of that goo out of the way, you can use the interface like a normal .NET type:

var aa = new ApplicationAssociationRegistration();

var iaar = (IApplicationAssociationRegistration)aa;

string myCurrentMp3Player = iaar.QueryCurrentDefault(".mp3", AssociationType.FileExtension, AssociationLevel.Effective);Behind the scenes, the runtime callable wrapper has to do something like this:

- Load in ole32.dll where COM functions reside.

- Call CoInitialize to initialize COM.

- Look up your CLSID and IID in the registry under HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT and find their associated DLL (in our case, “shell32.dll”)

- Create a factory for your class.

- Use the factory to create an instance.

- Call QueryInterface to get the specific interface we want (e.g. IApplicationAssociationRegistration)

- Get a pointer to the function we want using the vtable.

After all that, we finally have a place to jump to like we did with P/Invoke.

Why bother with all of this? One reason is that Microsoft has a huge legacy investment in C and C++ in Windows. There’s no compelling reason for them to rewrite things in .NET. A natural consequence is that the C++ code that implements their latest APIs will be exposed using COM for the foreseeable future. Recently, Microsoft has gone ahead and published .NET COM wrappers for some of the popular new APIs like the Libraries feature in Windows 7. With just a little work, you don’t have to wait on Microsoft to do this for you.

Given that .NET was designed as a successor to COM, it’s no surprise that Microsoft has made interoperability with it very seamless. The runtime callable wrapper does a good job of hiding most of the messier details. The garbage collector handles much of the bookkeeping involved with memory management that used to be the bane of COM programming. The runtime is very aware of typical COM semantics of when to allocate and free memory. It’s not always perfect. Sometimes you can be pre-emptive and force your COM object to be cleaned up via Marshal.ReleaseComObject so you don’t have to wait on the garbage collector, but you should be careful.

I just presented the basics of what I learned to get my job done. There’s a lot more out there for more advanced scenarios. I’ve found the free book “COM and .NET Interop” by Andrew Troelsen to be helpful.

There’s plenty of obscure Windows APIs out there for the taking. Enjoy!